Months ago in March, I visited University of California: Davis, and attended a MATH 17C lecture with a friend. This course parallels (partially) the Purdue course MA 16020; both are essentially “calculus with random advanced topics, targeted at non-stem majors.” The lesson was on the dot product and its applications to vectors and geometry in ; this was after the course had their one week crash course in linear algebra. Curricula aside, I found the lecture quite hard to follow. Having already learned the material, this difficulty was not from the topics, but the structure of the lecture. The lesson featured all the important (at least, what I consider important) parts of a lecture: motivation, derivation, explanation and examples, but the order made it impenetrable. There are undoubtedly many ways to poorly structure a lesson. Does there exist a correct way? I think so.

Discussion of terms

As my displeasure stems primarily from a math course, as well as other math courses, most of these terms come from mathematical literature. Some of these terms don’t readily apply to other academic fields (notably biology and composition); this will be discussed later.

- Motivation — Why should I care? Why does this matter?

- Derivation — Why is true? Where did it come from?

- Explanation — What does this actually mean?

- Examples — How do I actually use this?

In most fields, all of these elements must be present. A lecture lacking any of these is hopelessly dry and hard to follow.

Order

- Motivate the topic, but also write down the fact/equation/whatever.

- Explain each and every single term of the fact/equation/whatever.

- Explain why the fact/equation/whatever is true and where it came from quickly.

- Do some examples.

It’s hard to justify a proper order, but I feel like this makes sense. I’ll discuss important parts of each step in their own sections. (As a side note, I haven’t formatted my blog posts like so because I wrote this section last.)

Motivation must come early

I think this should go without saying, but lectures that fail to motivate the topic are not only boring, but actually a struggle to understand. In the words of Ravi Vakil,

When introduced to a new idea, always ask why you should care.

An incomplete(!) quotation from the preface of The Rising Sea, Foundations of Algebraic Geometry

If a lecture began with

Today we will be discussing the dot product of two vectors.

then we are in a much better position than many other lectures I have attended. Doing something like this makes a lecture easier to follow because I’ll know what to look for very early on. On the other hand, if this wasn’t mentioned and the professor wasn’t good at tying things together throughout the lecture, I would be dead in the water. I wouldn’t know what’s being taught or why.

We can still do better. The previous example makes clear the topic of the lecture, the dot product, but it doesn’t elaborate on why the dot product is useful or important. I suppose that this is a lesser issue (and well as being commonplace in mathematical lectures), but this isn’t too hard to remedy. After all, if you can’t justify why the topic you’re going to teach will be useful (at least in a superficial way), why is it being taught? Something such as

Today we will be discussing the dot product of two vectors

a formula that tells us how geometrically “close” two vectors are. We can use this to determine geometric equations in

.

is great. Not only will you know the topic being taught, you know a rough outline of the subtopics of the lecture.

The epigraph from the beginning of the section is incomplete. Vakil is generally quoted in its entirety with

When introduced to a new idea, always ask why you should care. Do not expect an answer right away, but demand an answer eventually.

Preface from The Rising Sea, Foundations of Algebraic Geometry

There’s a subtlety here, but it’s not too important in the context of most lectures and most courses. In courses where it’s common for a a lot of abstract tools and materials to be taught for some culminating result, it’s acceptable to say something like

Today we will be learning concept

, which will use later on with concept

, which will be used for application

.

Derivations are not always necessary

Taking a page from Evan Chen’s Napkin,

Natural explanations supersede proofs.

Understanding “why” something is true can have many forms. This is sometimes accomplished with a complete rigorous proof; in other cases, it is given by the idea of the proof; in still other cases, it is just a few key examples with extensive cheerleading.

Philosophy behind the Napkin approach

Derivations should only be included if they actually carry some insight with them. The classical proof of the dot product property

through the law of cosines doesn’t carry any insight with it. While an important property (in the context of calculus-III, the most important property), I imagine for most people the proof doesn’t actually make it any more memorable for people. This might just come from my divergence with pure math, but I don’t think most (that is, math classes for non-math majors) math classes should have full proofs in their lectures. They just aren’t very useful for people who will either not use advanced mathematics (I imagine most biology majors) or will only use math as a tool (virtually every non math STEM major). I see too many people frantically copying down proofs despite it not showing up anywhere. It won’t help with their understanding. If people want to know rigorous proofs, this should be assigned reading. Proofs just fail to be understandable in lecture settings (smaller classrooms are different).

It’s not that I’m against the ideas of proof. It’s obviously important that results are proven to be true and correct. My problem is that going over high-level proofs aren’t a good use of class time. Yet, instructors give derivations and proofs under a very understandable motivation: they want students to understand why something is true and where it comes from. This will make it easier to remember at the least; ideally, proof will give the student some aesthetic appreciation for the subject matter. But in a classroom with more than hundreds of kids that are here just to get good grades? This is pointless. In a course where students are required to synthesize the ideas to prove theorems, proofs belong. Otherwise they don’t. Memorization is okay.

There’s ways to give insight without full length proofs, too. I was explaining to a friend that one can find the power series of a given rational function

where, without the loss of generality, the degree of is less than the degree of

by rewriting

as

computing the power series of each term , then multiplying them through.

Depending on the course material, this might not be obvious. The alternative way is to decompose it with partial fractions and then sum the series (this is an equivalent method, but with addition instead of multiplication). But to justify this method, I gave the following “proof:”

- Let

be defined as the unique operator that takes a function

to its power series representation

.

- Since

maps functions to polynomials, all properties that are true for polynomials apply to

.

- As polynomials are closed under field operations (addition, multiplication and their inverses), all functions

are closed under field operations. In conversation I described this property as “linearity with respect to addition and multiplication.”

- Therefore

.

The key point is that this proof isn’t rigorous and there’s a lot holes in logic but that’s okay. Depending on the persons mathematical maturity, this proof gets across the main idea without having to be overly rigorous.

Multimedia explanations are a must

This is a particular problem in mathematical lectures, but I’ve always found that writing an expression on the board then giving a verbal explanations of all the important “parts” of the equation to be subpar. It surely works, but you run into problems trying to listen and write. This multitasking process can very easily become more difficult if the explanations/concepts are difficult, too. I think it would be more useful for lectures to annotate their notes while they explain it, like so:

It is inevitable that there exist students who will blindly copy down what’s on the board and not bother listening to the lecture itself. I think the holier-than-thou attitude of “so what? If they’re not going to listen, that’s their prerogative. They should be listening.” to go against the philosophy of teaching. Creating multimedia explanations bridge the gap for students that, from choice or not, don’t listen to lectures. And even for students that do listen, there’s a common problem where copying down slides that lack explanation leaves one with notes that can be unintelligible. Annotations go a long way to help.

This also has the added benefit that lecture notes of this form (although they don’t have to have arrows) are readily uploaded online for students to read.

Additionally, by setting the precedent of describing all the terms in a given expression (or theorem etc), students are more willing to ask questions. If some term is left unlabeled, students would be a bit more comfortable to ask for clarification, as there is now a (n arguably fair!) expectation for each and every term to be described.

Examples must contain motivation

Here’s an awful example of, well, an example:

This is terrible for someone trying to learn the course material. There’s a bunch of steps without any proper justification and on that note, there’s steps taken that lack motivation. What in the problem made you think to do this thing versus that thing? (The excuse for this is that this is actually a solution for a homework problem that I copied down, so motivation isn’t necessary, but this would be completely awful to read for someone’s first crack at the subject).

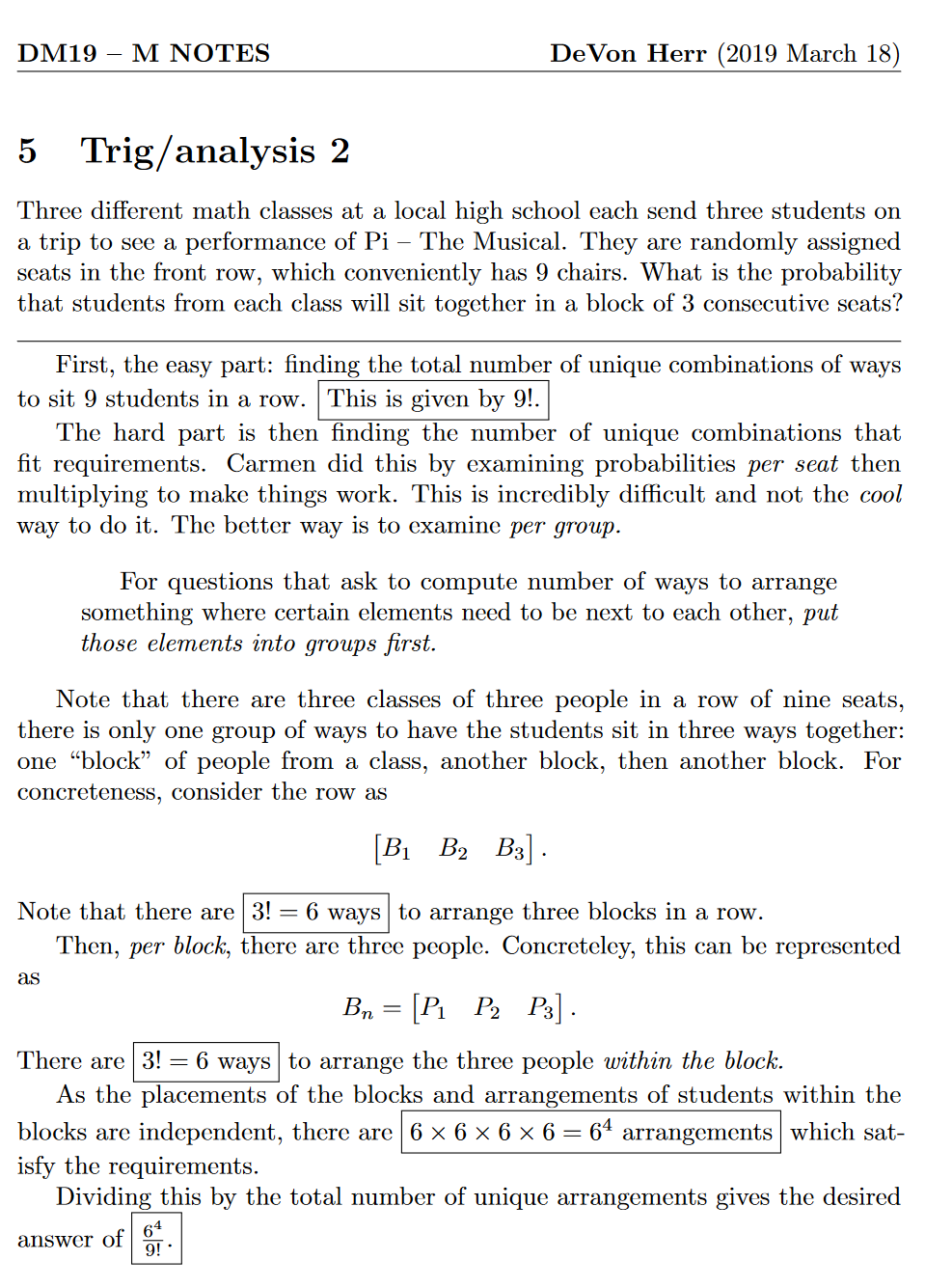

As an example of motivated explanation/solution, here’s an excerpt from my District 2019 March Notes,

It’s not the best and there’s definitely some meandering in my writing but there are elements of motivating the solution. Notably so the block

For questions that ask to compute the number of ways to arrange something where certain elements need to be next to each other, put those elements into groups first.

This is potentially obvious for someone who has experience in combinatorics, but that’s not the point. For someone who doesn’t, emphasizing such a statement is useful as the reader can “use” the statement in two meaningful ways:

- The solution now has a theme and narrative. Rather than guessing what each individual step is meant to do or accomplish, all steps lead back to this central idea.

- The reader can internalize the idea and (attempt to) use this idea for similar problems in the future.

Both of which I find very useful for the learning process. I’ve spoken about this before, but the absolute worst experience for an examination is to think “I’ve never seen this before and I have no idea how to start.”

Conclusion

People often aim their criticisms of difficult courses at their professors, lambasting them for poor lectures on difficult subject matter. While part of their criticisms don’t seem to be warranted, there definitely is some truth in the crux of their complaints. These improvements seem to be easy ways to substantially improve lectures.